Before Oregon had even attained statehood, what would become our home state had already passed various acts and laws forbidding African Americans from either living in the Oregon Country or moving into it. One even authorized the county constable to give non compliant black residents up to thirty nine lashes. The new state of Oregon ratified its Constitution in November of 1857, which per voter referendum addressed two issues relative to African Americans, both voted for by an overwhelming majority; Oregon would be a free state, where slavery was prohibited; and yet (ironically) Oregon’s Bill of Rights contained yet another exclusion law, right there in the text of our state’s highest legislation. Oregonians had decided their new state had no interest in the “peculiar institution” of slavery, yet wanted free African Americans living nowhere near them.

Historians often refer to Oregon, rightly as we see here, as having wanted to be a “white utopia,” a monoethnic and monocultural so-called “paradise.” Many of Oregon’s white settlers came to the territory from states where racism was a cultural and legislative institution, and they brought with them these mindsets of prejudice. This culturally institutionalized racial divisiveness has proven to be one of the greatest tragedies of Oregon’s history, in that its dark legacy has immensely damaged our ethnic and cultural diversity and our appreciation of it as a state.

Many Oregonians, Christians among them, did nothing to oppose the evils and injustice of racism. Salem’s own Asahel Bush, renowned businessman and citizen, was one of the most outspoken critics of abolitionism (an antislavery and pro-equality movement) and voice for anti-black sentiment. As its publisher, Bush frequently used the Oregon Statesman as a mouthpiece for his cultural and political views; in a June 13, 1851 editorial he wrote, presumably of those supporting equal rights,

“Their assertions that Negroes are entitled to approach our polls, to sit in our courts, to places in our Legislature are not more rational than a demand upon them that they let all bulls vote at their polls, all capable goats enjoy a chance at their ermine, all asses (quadrupled) the privilege of running for their General Assemblies and all swine for their seats in Congress.”

Though his assertions are blatantly racist and ignorant of the equality of all God’s people, Bush was not alone in his beliefs. Much of the Salem community agreed, whether they made their thoughts public or not. These early days were dark ones for the city of Salem.

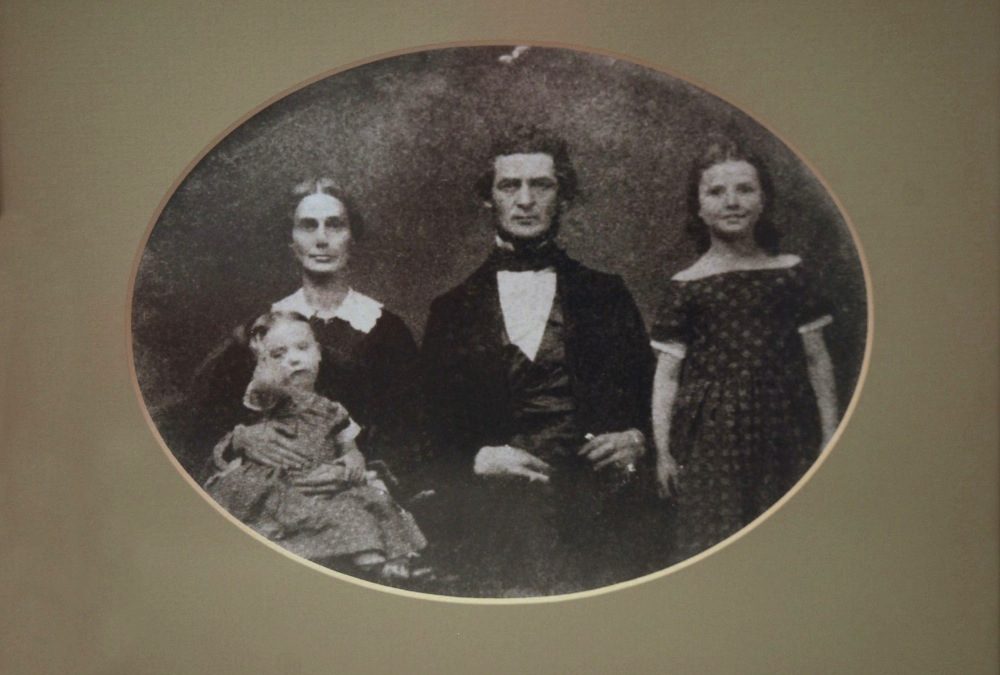

It was into this world that Reverend Obed Dickinson and his wife Charlotte arrived to preach the word of God. The Dickinsons came to Salem in late March of 1853, sent by the American Home Missionary Society so that Obed could pastor the newly-formed Salem Congregational Church. The two were recruited to head West by Rev. George Atkinson, who was convinced upon meeting Obed that he was the man to lead the young church. Obed preached his first sermon in Salem in the ramshackle schoolhouse that served as the Congregational Church building. Though the pouring rain trickled through the leaky roof onto the muddy dirt floor, the Dickinsons were surprised by a crowd of 40 that turned out to hear the new minister speak. Obed and Charlotte were optimistic about their work in Salem, and hopefully looked forward to what was to come. Their future was indeed destined to be central to Salem’s history, but not necessarily in the way they perhaps imagined.

Obed Dickinson was born on an Amherst, Massachusetts farm in the year 1818. Charlotte Humphrey was born a year earlier, also on a farm, in New York state. Charlotte would go on to be a schoolteacher for fifteen years, while her future husband would leave farm life to attend Marietta College in Ohio and then Andover Seminary back in Massachusetts. Eventually their paths crossed ways, and they were married on September 22nd 1852. Less than a month after their marriage, the two sailed aboard the Trade Wind with seven other missionaries sponsored by the American Home Missionary Society headed for the West.

Mid-voyage, the Trade Wind met with another vessel, the Navigator, and the Trade Wind’s passengers were allowed to journey aboard the adjacent ship. Charlotte records in a letter an encounter aboard the Navigator that is to us today significant as the first we see of the heartfelt love for the downtrodden that came to define the Dickinsons and their later ministry in Salem. The couple happened to encounter the Navigator’s cook, a black man who per Charlotte’s letter had quite the story to share. They listened attentively as he tearfully recounted a life marred by the treatment of a society who deemed him worthless. He asked for their prayers as they continued on their journey and as he continued his. “He is a Christian and I felt he is truly a child of Our Heavenly Father” wrote Charlotte. It did not matter that this man was black. The Dickinsons saw him for who he really was, a human being made in the image of God.

After their arrival in Salem, Obed’s letters to the Home Missionary Society expressed high hopes for the building of a new church. The attendance of the church had grown greatly from the original four-person congregation in the first months of his ministry. As time passed, construction on the new church began thanks to parishioner contributions. Obed had joined the local school board and become its director, spurred on by the poor condition of the schoolhouse that had doubled as the church’s home. The community largely respected the Dickinsons, though some disliked the reverend’s teachings on temperance.

It was known, however, that Obed stood on the unpopular side of what was deemed the “negro question.” The Dickinsons openly welcomed and appreciated Salem’s black community.Charlotte even opened their home as a school a few days a week for a handful of illiterate black women. Obed fearlessly used the pulpit as well as day-today conversations as a means of denouncing the mistreatment of African Americans. The church began to attract black parishioners (it’s estimated Salem’s entire black population at the time was no more than seventeen), to the chagrin of some church members. Obed denied requests for a “separate meeting” for African Americans, saying “Christ had given us no warrant for such distinctions.” With war largely over the issue of slavery on the horizon, and talks of Oregon’s secession lingering, the Dickinsons’ stance for justice became increasingly controversial.

They, however, had no intention of giving way. On June 16th, 1859, Obed delivered a sermon on Matthew 25:40, “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.” He condemned the fact that blacks were forced to pay taxes and yet could not send their children to public school. In February of 1862 he sent a detailed and lengthy report of Salem’s abuses of African Americans to the Home Missionary Society, mentioning among them the story of a young boy who was accused of robbery without evidence. He was hung from a tree and tortured for the better part of three days and then locked in jail for two months before finally being acquitted.

The Dickinsons’ greatest scandal came in January of the following year, when Obed married Richard Bogle and America Waldo, both black. The wedding was a sizeable event, well-attended by both blacks and whites. Many in the community were quickly up in arms, aghast that such a controversial event would take place in their hometown. Asahel Bush both publicly and privately decried the wedding, saying among other things that it was “regarded as shameful by the community.”

Through all this, Obed’s congregation began to side against their minister. One prominent donor told him that if he didn’t cease speaking on such “exciting topics” that he would lose his $500 regular contribution, a massive sum at that time. The Dickinsons had struggled financially since very early in their Salem residency. Obed had built their small home himself on rural property far cheaper than a preexisting home. The couple were constantly in debt in order to make ends meet. Food was in short supply, and they let nothing go to waste. Matters were made worse by dwindling funding from the Home Missionary Society as Obed was expected to slowly increase funding from his congregation. Requests for more money were a regular theme of his reports to the Society. The Dickinsons, however, did not waver. “This stubborn determination to persist,” says Egbert S. Oliver, an expert on the Dickinsons, “is the mark of Dickinson’s ministry.”

“I shall have little sympathy from the people among whom I labor,” wrote Obed himself, “but I feel assured that there is one above who does sympathize with me.”

After a series of resolutions, resignations, and reinstatements, Obed Dickinson stepped down from the pulpit at Salem Congregational Church for the last time in March of 1867. He had tired of battling his congregants, and more so could no longer provide for he and his wife with his meager earnings. Obed would go on to develop the seed and gardening supply business he had started on the side into a prosperous small business. But even as he finally found worldly sustenance, it was still the commitment to truth and justice that he and Charlotte shared that would truly define them, and that would forever leave its mark on the Salem community. Their steadfast adherence to preaching Christ’s love for all people is what marks them as some of our city’s greatest heroes.

“Nobody but those who have tried it can know the delight it gives us to help those whom no one else cares for,” wrote Obed in one of his reports. “We feel that when man casts out and tramples under foot the poor of the earth then God takes up their cause, and pleads for them. The smile of God gives a warmth and gladness to our hearts which more than repays for all the trouble.”

References:

- Oliver, Egbert S. “Obed Dickinson and the “Negro Question” in Salem.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 92 (1991). Print.

- Dickinson, Obed, and Egbert S. Oliver. Obed Dickinson’s War against Sin in Salem, 1853-1867: Reports to the American Home Missionary Society. Portland: Hapi, 1987. Print.

- Perseverance: A History of African Americans in Oregon’s Marion and Polk Counties. Salem: Oregon Northwest Black Pioneers, 2011. Print.

- “Charlotte Dickinson.” Salem (Oregon) Online History. Salem Public Library. Web. 29 Aug. 2015.

- Lynn, Capi. “Minister Braved Racist Backlash.” Statesman Journal 17 Feb. 2007. Gannet. Web. 29 Aug. 2015.